History

Coronavirus Coverage

March 27, 2020

How some cities ‘flattened the curve’ during the 1918 flu pandemic

Social distancing isn’t a new idea—it saved thousands of American lives during the last great pandemic. Here's how it worked.

By Nina Strochlic and Riley D. Champine

Social distancing isn’t a new idea—it saved thousands of American lives during the last great pandemic. Here's how it worked.

By Nina Strochlic and Riley D. Champine

Philadelphia

detected its first case of a deadly, fast-spreading strain of influenza

on September 17, 1918. The next day, in an attempt to halt the virus’

spread, city officials launched a campaign against coughing, spitting,

and sneezing in public. Yet 10 days later—despite the prospect of an

epidemic at its doorstep—the city hosted a parade that 200,000 people

attended.

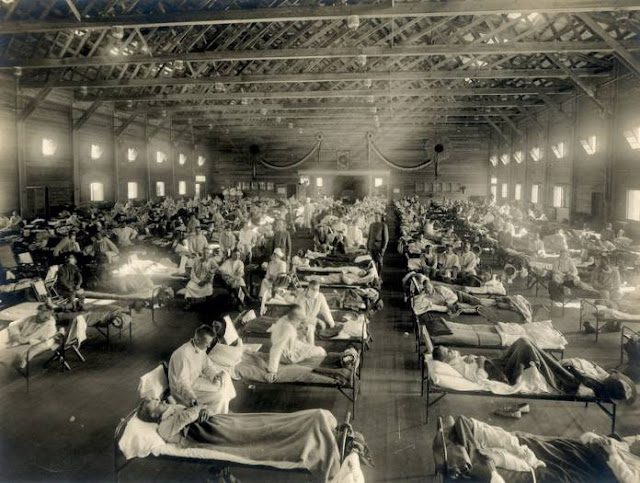

Flu cases continued to mount until finally, on October 3, schools, churches, theaters, and public gathering spaces were shut down. Just two weeks after the first reported case, there were at least 20,000 more.

The 1918 flu, also known as the Spanish Flu, lasted until 1920 and is considered the deadliest pandemic in modern history. Today, as the world grinds to a halt in response to the coronavirus,

scientists and historians are studying the 1918 outbreak for clues to

the most effective way to stop a global pandemic. The efforts

implemented then to stem the flu’s spread in cities across America—and

the outcomes—may offer lessons for battling today’s crisis. (Get the latest facts and information about COVID-19.)

From its first known U.S. case,

at a Kansas military base in March 1918, the flu spread across the

country. Shortly after health measures were put in place in

Philadelphia, a case popped up in St. Louis. Two days later, the city

shut down most public gatherings and quarantined victims in their homes.

The cases slowed. By the end of the pandemic, between 50 and 100

million people were dead worldwide, including more than 500,000

Americans—but the death rate in St. Louis was less than half of the rate

in Philadelphia. The deaths due to the virus were estimated

to be about 358 people per 100,000 in St Louis, compared to 748 per

100,000 in Philadelphia during the first six months—the deadliest

period—of the pandemic.

Dramatic demographic shifts in the past century have made containing a

pandemic increasingly hard. The rise of globalization, urbanization,

and larger, more densely populated cities can facilitate a virus’ spread

across a continent in a few hours—while the tools available to respond

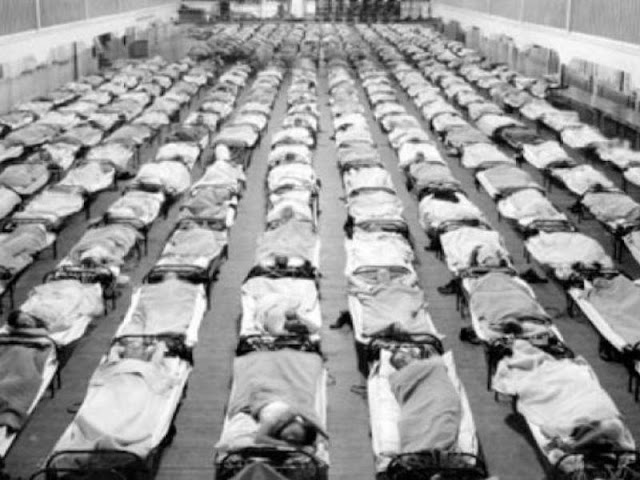

have remained nearly the same. Now as then, public health interventions

are the first line of defense against an epidemic in the absence of a

vaccine. These measures include closing schools, shops, and restaurants;

placing restrictions on transportation; mandating social distancing,

and banning public gatherings. (This is how small groups can save lives during a pandemic.)

Of course, getting citizens to comply with such orders is another story: In 1918, a San Francisco health officer shot three people

when one refused to wear a mandatory face mask. In Arizona, police

handed out $10 fines for those caught without the protective gear. But

eventually, the most drastic and sweeping measures paid off. After

implementing a multitude of strict closures and controls on public

gatherings, St. Louis, San Francisco, Milwaukee, and Kansas City

responded fastest and most effectively: Interventions there were

credited with cutting

transmission rates by 30 to 50 percent. New York City, which reacted

earliest to the crisis with mandatory quarantines and staggered business

hours, experienced the lowest death rate on the Eastern seaboard.

In 2007, a study in the Journal of the American Medial Association

analyzed health data from the U.S. census that experienced the 1918

pandemic, and charted the death rates of 43 U.S. cities. That same year,

two studies published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

sought to understand how responses influenced the disease’s spread in

different cities. By comparing fatality rates, timing, and public health

interventions, they found death rates were around 50 percent lower in

cities that implemented preventative measures early on, versus those

that did so late or not at all. The most effective efforts had

simultaneously closed schools, churches, and theaters, and banned public

gatherings. This would allow time for vaccine development (though a flu vaccine was not used until the 1940s) and lessened the strain on health care systems.

The studies reached another important conclusion: That relaxing

intervention measures too early could cause an otherwise stabilized city

to relapse. St. Louis, for example, was so emboldened by its low death

rate that the city lifted restrictions on public gatherings less than

two months after the outbreak began. A rash of new cases soon followed.

Of the cities that kept interventions in place, none experienced a

second wave of high death rates. (See photos that capture a world paused by coronavirus.)

In 1918, the studies

found, the key to flattening the curve was social distancing. And that

likely remains true a century later, in the current battle against

coronavirus. “[T]here is an invaluable treasure trove of useful

historical data that has only just begun to be used to inform our

actions,” Columbia University epidemiologist Stephen S. Morse wrote in an analysis of the data. “The lessons of 1918, if well heeded, might help us to avoid repeating the same history today.”

Nina Strochlic is a staff writer covering culture for National Geographic.

Follow Nina

Fonte: National Geographic,

STROCHLIC, N. & CHAMPIRE, R. D. (2020). How some cities ‘flattened the curve’ during the 1918 flu pandemic. National Geographic, March 27, 2020. History, Coronavirus Coverage. National Geographic Society.

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário

Não serão aceitos comentários ofensivos, preconceituosos, racistas ou qualquer forma de difamação.